3 Background

Closed-loop control in neuroscience

Mesoscale neuroscience—on the level of populations of neurons, rather than the whole brain or individual cells—is currently undergoing a revolution fueled by advances in neural manipulation (1–8) and measurement (9–16) technologies as well as data analysis methods (17–22). These have yielded unprecedented datasets (23, 24) and insights into network activity and plasticity (25–29) Moreover, they enable novel experimental paradigms such as direct closed-loop control of neural activity (30–39). This closed-loop stimulation offers exciting prospects of intervention in processes that are too fast or unpredictable to control manually or with pre-defined stimulation, such as sensory information processing, motor planning, and oscillatory activity. Unlike other forms of closed-loop control using environmental/stimulus input (40), behavioral output (41) or neurofeedback training (8, 42), the direct control of neural activity itself provides more opportunities for revealing the downstream effects of that activity.

Closed-loop control of neural activity can be implemented in an event-triggered sense (37–39)—enabling the experimenter to respond to discrete events of interest, such as the arrival of a traveling wave (43) or sharp wave-ripple (44)—or in a feedback sense (33–36), driving the system towards a reference state or trajectory. The latter has multiple advantages over open-loop control (delivery of a pre-defined stimulus): by rejecting exogenous inputs, noise, and disturbances, it reduces variability across time and across trials, allowing for finer-scale inference. Additionally, it can compensate for model mismatch as it actively reduces error, whereas an open-loop stimulus is defined and limited by imperfect models. Moreover, whereas traditional perturbation methods often include lesioning (45), unnatural silencing, or extreme stimulation, feedback control poses a more naturalistic alternative. Clamping the activity of a population of neurons to their baseline, for example, effectively shuts down information flow from those neurons without departing from typical firing rates.

Various scales and tools for closed-loop control

Closed-loop control of neural activity can be performed at multiple scales and with different sets of tools. At the smallest, sub-neuron scale, feedback control has yielded decades of fruitful research in the form of tools such as the voltage clamp (46) and dynamic clamp (47, 48), controlling electrical properties of the cell membrane. The frontiers of this small-scale neuroscience often involve scaling up to many neurons and scaling down to subcellular structures such as dendrites, but multi-electrode, in-vivo, intracellular recording methods are challenging (49–53). Optical tools—e.g., optogenetics and fluorescence microscopy—can circumvent the difficulties of working with electrodes at such small scales, but an optical approach is not yet feasible for this purpose. The obstacles lie mainly in recording technology: the kinetics of both voltage indicators (16) and intracellular calcium (54) are too slow to capture phenomena faster than a typical action potential.

By contrast, the current state of technology is ripe for innovating closed-loop control methods at larger scales of neural activity, from single neurons to populations and circuits. Several promising combinations of recording and stimulation modalities are possible and still relatively novel: electrode recording with optogenetic stimulation (33–35, 55), fluorescence microscopy with electrical stimulation (16), fluorescence microscopy with photostimulation (all-optical control) (36, 56–59), and fMRI with optionally transcranial photostimulation (60, 61). Each of these tool combinations has pros and cons in terms of spatial and temporal resolution, crosstalk (62), and degrees of freedom. A natural starting point for many neuroscientists is the first of these tool sets—electrode recording combined with optogenetics—since the two methods are so widely used, interfere little with each other (as long as metal electrodes are not directly illuminated (55, 62)), and allow for genetically targeted stimulation. I will henceforth refer to this combination as CLOC, following the convention established by previous works (34, 35).

Previous work

The proposed work builds on the work my lab and collaborators have done previously in developing CLOC. This includes pioneering work taking feedback control from the cellular to the network level by controlling population firing rates in vitro—first by (63), who reduce unnatural global bursting and conclude as a result that such bursting results from the lack of the exogenous input present in the live, awake cortex. Later, (64) used the same proportional error-driven controller in a demonstration of user-friendly real-time electrophysiology software.

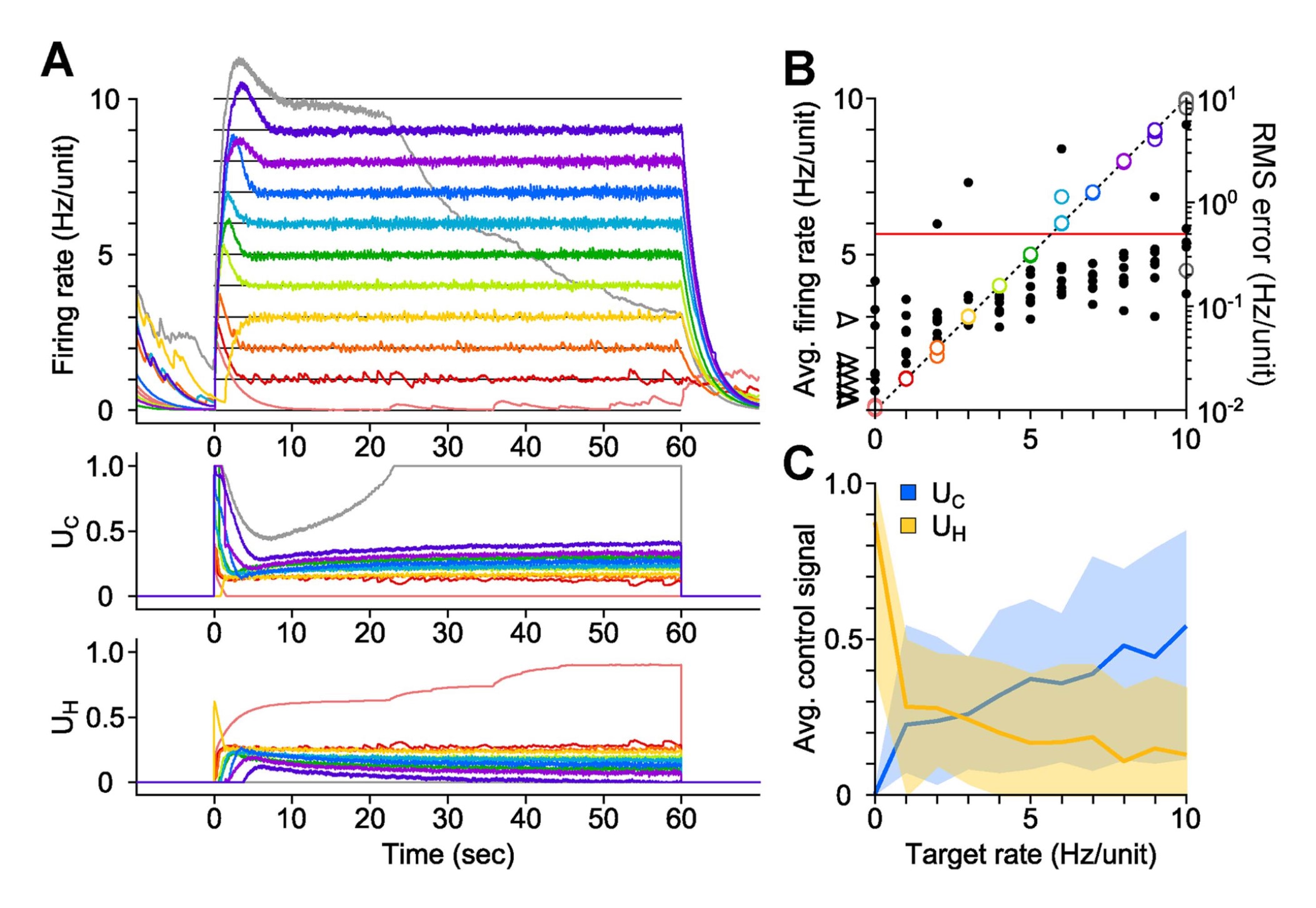

These model-free control methods later saw further development and the introduction of optogenetic actuation. In the first known demonstration of optogenetic feedback control, (33) used bidirectional stimulation for fixed and slowly varying firing rate targets in vitro (Figure 3.1 (a)). The authors improved control methods by an introducing an integral term to the model-free controller and, in another first, demonstrated feedback control of firing rates in vivo by bringing CLOC to the anesthetized rat. (34) used PI control again, but developed a more principled approach to set estimation and control parameters and tracked dynamic firing rate trajectories down to a ~100-ms timescale (Figure 3.1 (b)).

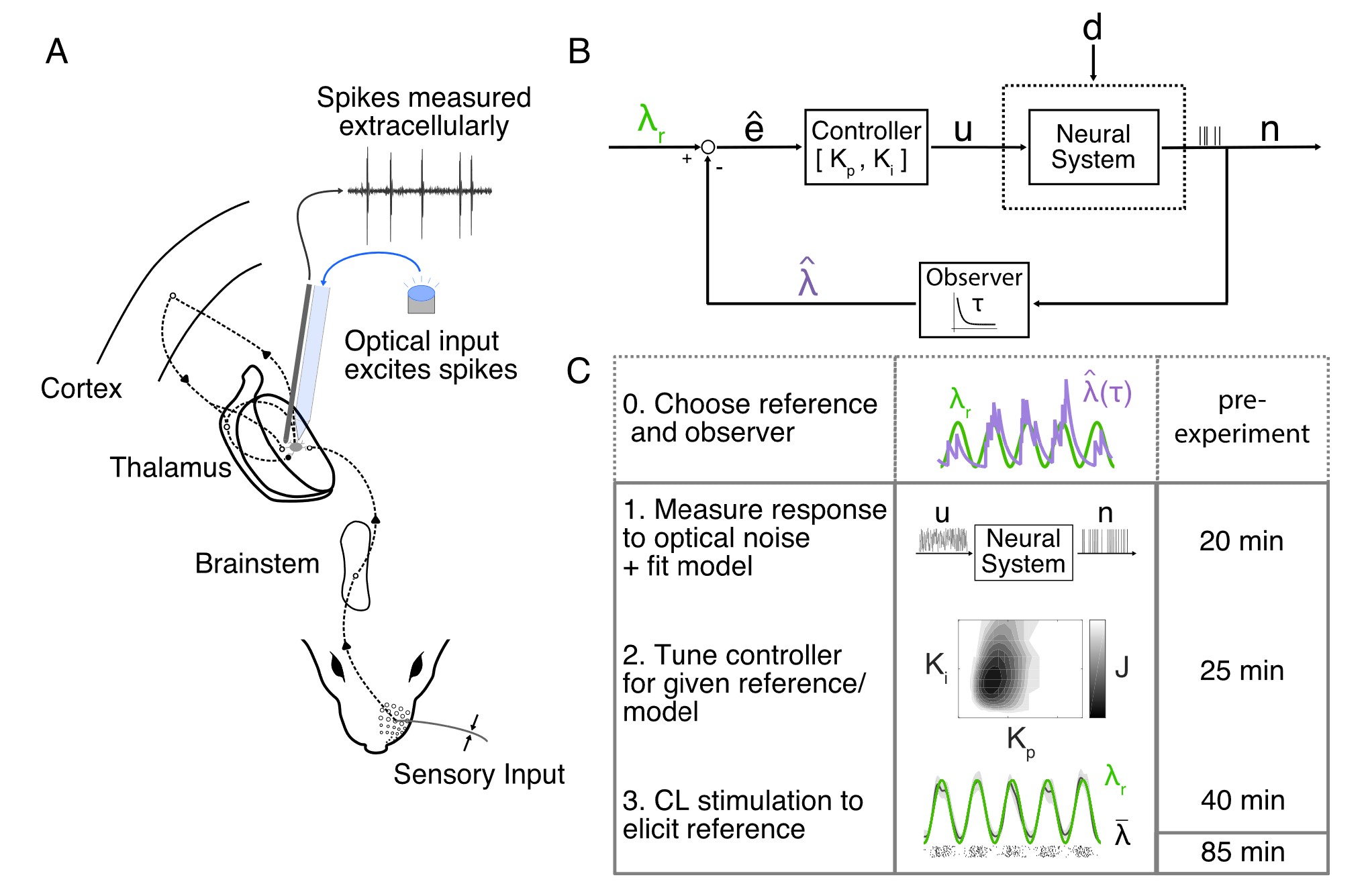

Later, in a direct precursor to the proposed work, (35) employed more sophisticated and scalable optimal feedback control methods that can be characterized as an adaptive linear quadratic regulator (LQR). Built on a state-space, linear dynamical system model, the controller estimates the latent state using Kalman filtering (65) and calculates in real-time the optimal control input based on the current error. The authors enable adaptivity by estimating a second latent state, added to the first, that represents a slowly varying bias or disturbance to the system—important especially in awake animal experiments, where dynamic brain state changes contribute to high per-trial variability (Figure 3.1 (c)).

Unexplored applications for network-level control

While preliminary technological foundations for feedback control of neural activity have already been laid, CLOC has yet to be applied to network-level variables beyond population firing rates to further causal hypothesis testing. Examples of these potential targets for control include the activity of different cell types (66–71); the type (72–74), frequency (75), amplitude (75), spike coherence (76, 77) and interactions (78, 79) of different oscillatory patterns (80); discrete phenomena such as bursts (81), sharp wave ripples (44), oscillatory bursts (82–86), traveling waves (36, 43, 87–90), or sleep spindles (91); and latent states describing neural dynamics (92–99), including those most predictive of behavior (20, 100, 101). In the proposed work, I focus on the latter for their success in generating computational hypotheses for brain function and in predicting behavior. In the following chapters, I describe plans to move towards in-vivo control of latent dynamics by developing CLOC infrastructure and algorithms and finally performing simulations and analysis in silico.